Midweek Massacre #4: Tim Burton's "Sleepy Hollow."

Representations of Witchcraft and Religious Violence

Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, yet it has not received the critical attention warranted, both within film studies and Horror Studies, at large. More surprisingly, there has yet to be a renewed interest in several cinematic tropes, outside of the usual analyses of stylizations of witchcraft captured within the film.

Filmed before there was a renewal in patriarchal criticism, Sleepy Hollow represents a significant backstory, particularly taking place in Ichabod Crane’s childhood. While the original story by Washington Irving doesn’t indicate any kind of familial trauma beheld by Crane, gratefully Burton wrote in the backstory, providing beautifully apt tension within the adult Crane. Having fancied himself a pioneer of forensic science in NYC at the turn of the 18th-century, Crane is tasked to investigate several beheadings. What is most notable are the daydreams and nightmares he encounters on his journey and during his investigation at Sleepy Hollow.

Our first introduction to Ichabod’s mother is during a fainting spell, of which he frequently has in the movie. Within this scene, the Crane cottage seems to be out of a fairytale, with the young Crane gifting his mother flowers. In turn, she uses these flowers at a hearth, and begins scrying in the dirt arcane etchings. The allusion is to her knowledge of white magic, primarily nature-based. Contrasting this is his father, attired in colonial-era clergy clothes, as well as flashed of a red door against a churches white walls. Yet, when the red door opens, Crane wakes with a start.

Scene two occurs during yet another fainting spell, with a focus on his mother within a natural setting for a second time. As Crane enters the grove where his mother is communing with nature, she and Crane experience a shared magic, as well as the levitation of his mother. Again, Burton contrasts this with the aggressive exercise of colonial patriarchal suppression, with Crane’s father wordlessly condemning his mother by gesturing at the arcane scrye and then at an undisclosed passage of Christian scripture. At this, the audience is given a clearer glimpse into the red-doored room, where there is a flash of his mother within an iron maiden.

Lastly, we are given the why of Ichabod’s scarred hands, which are covered in puncture marks. During a fevered dream, literally, the young Ichabod explored the room of torture, where (among other medieval devices) his mother is imprisoned in the iron maiden. When our young protagonist becomes frightened at the sight of his mother imprisoned, he jumps and lands on the Iron Chair, thus acquiring punctured scars on his palms. He subsequently bears witness to the iron maiden bursting open, spilling his mother’s blood across the threshold.

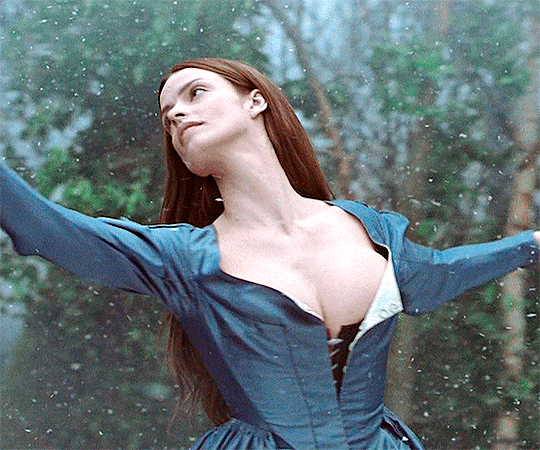

So, given these nightmares, the matured Ichabod focuses solely on reason and logic, not only in his detective work, but within his personal life. That is until Katrina Van Tassel becomes an intertwined part of his story. As you can imagine, Katrina is also practiced in the art of natural magic and benevolent witchcraft. While her presence awakens the memories that Ichabod would have liked to have left behind in his childhood, Ichabod initially is guarded and suspicious of any good gestures by the kind Katrina.

Given the nightmares, the avoidance of any style of magic that would remind Crane of his mother, and his focus on logic and reason, one can conclude that Crane’s traumatic childhood drove him not only from anything related to magic (natural or otherwise), but from any kind of religious adherence whatsoever. Notably, the inclusion of Lord Crane, the zealous patriarchal preacher, provides an apt critique by Burton of the violence leveraged against those accused of witchcraft, whom were primarily women. As Ichabod’s mother was horrifically murdered by his father, the inclusion of Lady Crane would have not served any further purpose unless a similar character, such as Katrina, was introduced early in the film.

As such, this revision of the original short story by Washington Irving takes into account a dark truth in American history, in that the reality of the horror is not in the Headless Horseman (once a Hessian mercenary), but in the patriarchal suppression of non-christian belief systems, as well as the oppression of women in the 1700s onward.

What a great look at Burton's Sleepy Hollow. Now I need to watch it again!